Traveling to high altitudes offers breathtaking views and unforgettable adventures. But if you’re not careful, it can leave you breathless—literally.

In this article, you will discover what altitude sickness is, how it can escalate into severe conditions, and how to protect yourself.

As a travel medicine specialist and passionate traveler, I’ll share science-backed advice, real-world tips, and must-know strategies. Keep reading—your health (and trip) might depend on it!

In This Article

This post includes affiliate links. If you choose to purchase through these links, I may receive a commission, helping me continue creating valuable content for you. This comes at no additional cost to you.

We receive a fee when you get a quote from World Nomads using links in this post. We do not represent World Nomads. This is not a recommendation to buy travel insurance.

Why Altitude Matters for Travelers?

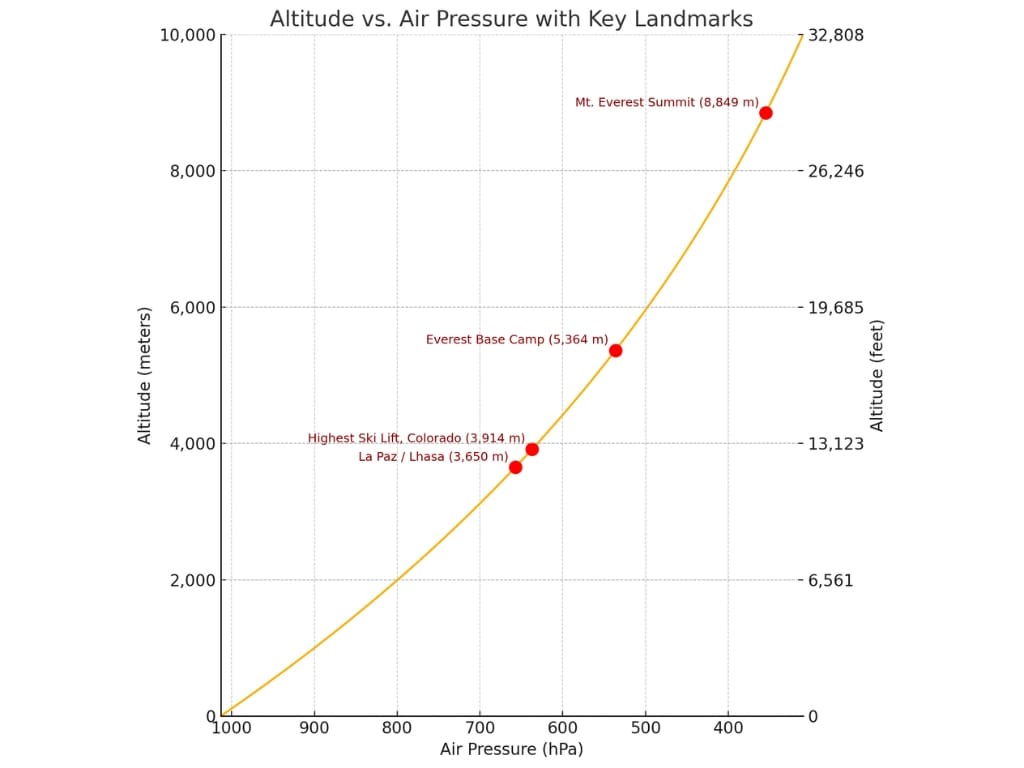

You don’t have to summit Everest to experience altitude sickness. Symptoms typically arise in altitudes over 2500 meters (8202 feet), but it can be just 1800 meters (5905 feet) in sensitive individuals.

Many popular destinations, such as Cusco (3,399 meters/11,152 feet), La Paz (3,640 meters/11,942 feet), and Colorado ski resorts, sit well above 2,500 meters (8,200 feet).

Studies show that up to 40% of travelers develop at least mild symptoms at moderate altitudes, and the chance rises with higher altitude and faster ascent.

Flying directly to high elevations without acclimatization dramatically increases risk.

What is Altitude Sickness? Why is The Air Thinner in Higher Altitudes?

Let’s start with a very short explanation of the physics. You can imagine a column of air from the Earth’s surface to the edge of our atmosphere.

The air pressure is caused by the weight of the air above you. This means the higher you go, the fewer and fewer air molecules are above you; therefore, there is less weight and lower air pressure.

And because the atmosphere layer is very thin compared to the size of the Earth, you can experience it easily (most countries have at least one peak over 2,500 meters/8,202 feet).

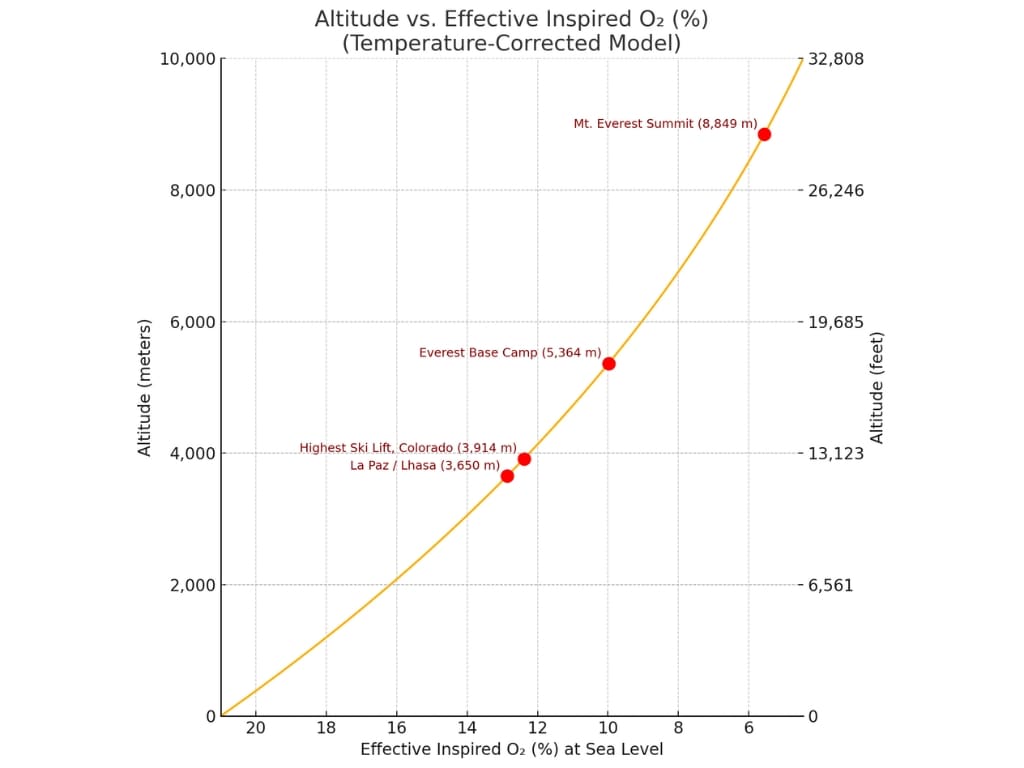

The oxygen fraction stays the same; what changes is the pressure of oxygen in the air. The pressure of the inspired air is even lower because of the water vapor pressure in the airways. (You exhale at least 0.4 liters of water per day.)

In short: Higher altitude = fewer air molecules above = lower atmospheric pressure.

That means breathing the same fraction of oxygen (21%) in the air in La Paz, Bolivia, is equivalent to breathing 12% oxygen at sea level.

What Happens to Your Body at High Altitude? Acclimatization explained.

The symptoms of Altitude sickness are mostly a result of your body responding to hypoxia (low oxygen levels). They depend on how fast the onset of hypoxia is and how deep it is. For example, sudden exposure to an altitude equivalent to the summit of Mt. Everest would result in unconsciousness within 2 minutes.

In minutes and hours:

The body’s first reaction is similar to hypoxia induced by physical activity.

First, increased volume of breaths, then frequency. At the same time, the heart rate rises.

In the lungs, small vessels constrict to improve the exchange of oxygen and CO2.

In hours to days:

The brain constitutes just 2% of body weight and consumes 20% of oxygen. To keep up with the demand, blood flow increases, which can cause headaches.

The hyperventilation causes more CO2 to be exhaled, causing changes in blood pH (acid-base balance). The pH imbalance then stops further increases in the frequency of respiration. This is compensated by the kidneys in a few days, allowing ventilation to remain high.

This mechanism is often the one that helps the symptoms go away, and it’s also the one targeted by medication.

In blood, the volume of plasma is reduced, and the hemoglobin (protein transporting oxygen) concentration is higher.

In weeks:

Tissue metabolism is adjusted. More red blood cells are being produced.

The long-term acclimatization mechanisms are coordinated by HIF – hypoxia-inducible factor in every human cell.

Because of the genetic variability of this factor, different people acclimate at various paces. That’s why your or your close family’s previous experience at altitude will predict your future ability to acclimate, while physical fitness has little to no effect.

Understanding Altitude Sickness: From Mild to Life-Threatening

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)

Mild AMS symptoms typically start within 6 to 24 hours of arrival at high altitude, often after the first night’s sleep. They result from brain tissue hypoxia and the compensatory increase of blood flow to the brain.

People often describe their feelings as similar to a hangover. They usually resolve in 1 to 2 days.

Watch for:

- Headache (most common)

- Nausea or vomiting

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Fatigue

- Sleep disturbances

High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE):

HACE is a life-threatening form of AMS caused by brain swelling from hypoxia. Symptoms include:

- severe confusion

- ataxia (clumsiness and difficulty walking straight)

- hallucinations

- coma

HACE can worsen within hours and be fatal, making immediate descent and oxygen therapy essential.

The rules:

- No further ascent until symptoms resolve

- Use medication

- Descent to a lower altitude if the symptoms don’t improve with medication

- If any sign of HACE is present, descent immediately.

Treatment:

Descent

The best treatment for any symptom of altitude sickness is descent. However, it should be without exertion (easy walk downhill, helicopter evacuation), which is not always possible.

Hyperbaric chamber

The hyperbaric chamber mimics descent by pressurizing the air inside it. It can be found in some high-altitude medical centers. Portable chambers with a simple pump system are also used in camps.

Oxygen

The fastest way to relieve symptoms, but it is temporary.

Medication:

Acetazolamide speeds acclimatization by inducing the mechanisms for acclimatization in the kidneys in 8 to 24 hours instead of 4 days.

Dexamethasone rapidly reverses symptoms (2-4 hours) by reducing swelling, but doesn’t improve acclimatization.

Acetaminophen and Ibuprofen help with headaches.

High altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE)

The vessels bringing blood to the lungs constrict to help exchange gases more efficiently. In addition, capillaries in less oxygenated parts of the lungs constrict, and those in well-oxygenated parts dilate. If this mechanism continues for a long time or is exaggerated, fluid leakage can occur, causing pulmonary (lung) edema.

It typically occurs on the 2nd to 4th day at a new high altitude, especially after rapid ascent. The incidence overall is low (less than 1% of travelers to 3,500m/ 11,482 feet or more). It’s the leading cause of altitude-related death.

Symptoms include:

- decreased performance

- extreme breathlessness

- chest tightness

- dry cough, later productive cough with pink frothy fluid, or even blood

The rules after having symptoms of HAPE are the same as those for AMS and HACE, only now the situation is more serious.

Descending at least 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) is extremely important, as other interventions are less effective. Although the symptoms may resemble pneumonia at high altitudes, it’s always HAPE until proven otherwise.

Treatment:

- descent without exertion

- oxygen

- hyperbaric chamber

Medication:

Not as effective as in AMS and HACE.

Nifedipine, Tadalafil, Sildenafil, and Dexamethasone showed some effect.

Proven Ways to Prevent Altitude Sickness

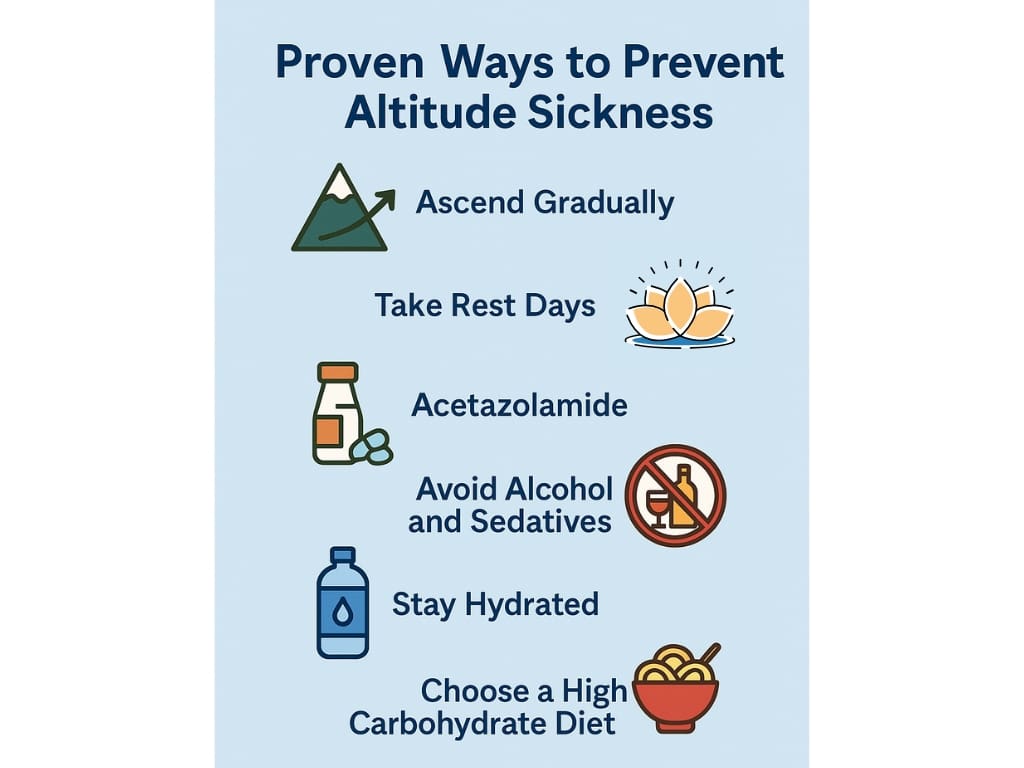

- Ascend Gradually:

Increase sleeping elevation by no more than 300-500 meters (984-1,640 feet) daily above 3,000 meters (9,843 feet). Ascending more during the day, but returning down to sleep is beneficial.

On hiking routes, travelers are often dependent on the next accommodation. Try to keep the average daily elevation gain within the safe zone. For example, resting for a day after ascending 1,000 meters (3,280 feet). - Take Rest Days:

Rest for a day after every 3 to 4 days of climbing. - Acetazolamide:

Begin one day before ascent, and continue for at least 48 h after arrival at the highest altitude. It enhances acclimatization by stimulating breathing.

It’s recommended for travelers with a history of AMS or when rapid ascent is unavoidable. That includes flying from low altitude to cities over 3000 meters (9,843 feet).

It can’t be recommended for everyone for prevention (diabetics, allergies, etc.), but it should be in a high-altitude traveler’s medical kit. - Other medication:

In some cases, dexamethasone can be used as an alternative for AMS prevention, but it is inferior and has more side effects than Acetazolamide. Ibuprofen can also be used, but it is inferior and doesn’t help acclimatization. - Avoid Alcohol and Sedatives:

They depress respiration, worsening hypoxia during sleep. - Stay Hydrated:

Maintain hydration, but avoid over-drinking, which can cause hyponatremia (low sodium levels). - Choose a high-carbohydrate diet:

Carbohydrates store more energy per unit of oxygen needed.

Other Health Risks at High Altitude

Cold-Related Illnesses:

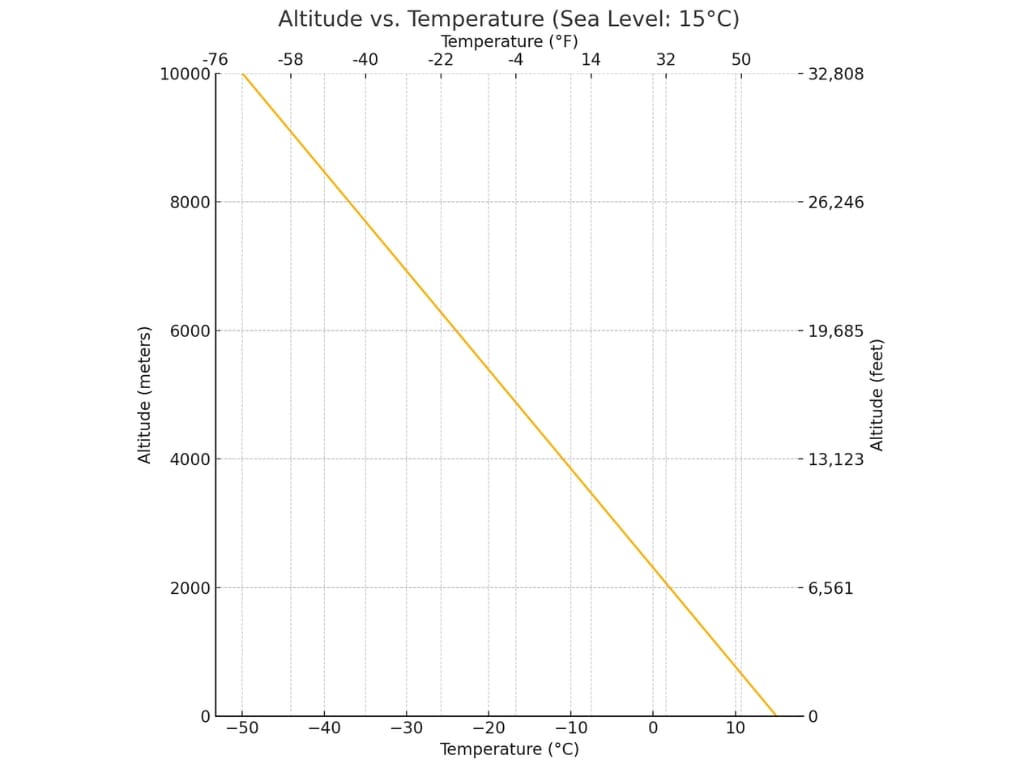

Hypothermia and frostbite risk increase with ascent, as the temperature decreases by 6.5 °C (43.7 °F) per 1,000 m (3,280 ft) on average.

Ultraviolet (UV) Radiation Risks:

UV radiation increases by 4% per 300m (984 feet) gain in altitude.

Sunburn – use proper UV-blocking sunscreen

Snow blindness (UV keratitis) is painful but self-limited and without sequelae. It is treated with antibiotic ointment, pain relievers, and an eye patch. It is usually resolved in less than 2 days. It is preventable by wearing UV-absorbing sunglasses.

Low humidity:

Dehydration is caused by increased water loss through breathing and the skin.

Sore throat, cough, and dry skin.

High-altitude retinal hemorrhage (bleeding) (HARH) is common and usually asymptomatic.

Special Considerations for Travelers with Chronic Illnesses

Groups having the same or lower risk as the average adult:

Children, people with allergic asthma, people with well-controlled seizure disorder on medication, and healthy adults over 60 years old.

Groups at higher risk should be cautious in high altitudes and consult their doctor before travel:

People with any chronic lung disease, especially pulmonary hypertension and COPD; People with sickle cell trait; People with a history of seizure, currently not on medication;

Diabetics; Travelers with retinopathy; people with moderate heart conditions (arrhythmias, hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure…), and women using oral contraceptives.

Groups with substantial risk, advised not to travel to high altitudes:

Infants 6 weeks and younger residing in low altitude, people with severe COPD, or any unstable or severe lung or heart disease, people with sickle cell anemia, and women with high-risk pregnancy.

Summary

Altitude sickness is largely preventable with basic knowledge you’ve just learned and smart preparation.

If you won’t be able to prevent the sickness, don’t push your limits and follow the recommendations, especially stopping the ascent and descending if your problems worsen.

Also, remember proper insurance covering medical evacuation, including emergency helicopter rides and mountain activities, because the bill can get extremely expensive.

You can check out World Nomads’ Travel Insurance for Hiking and Trekking Adventures and get a free quote for your trip.

Respect the mountains, listen to your body, and travel smart.

For more expert travel health insights, explore my other blogs. Your next adventure deserves the best start.

Resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Jeffrey B. Nemhauser, CDC Yellow Book 2024: Health Information for International Travel (New York, 2023; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 Mar. 2023), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197570944.001.0001

Travel Medicine, 4th Edition – December 13, 2018, Authors: Jay S. Keystone, Phyllis E. Kozarsky, Bradley A. Connor, Hans D. Nothdurft, Marc Mendelson, Karin Leder, Language: English, Hardback ISBN: 9780323546966

Luks, A. M., Auerbach, P. S., Freer, L., Grissom, C. K., Keyes, L. E., McIntosh, S. E., … & Hackett, P. H. (2019). Wilderness medical society clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of acute altitude illness: 2019 update. Wilderness & environmental medicine, 30(4_suppl), S3-S18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2019.04.006

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this blog post is for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any health problem. The use or reliance on any information provided in this blog post is solely at your own risk.