Traveler’s thrombosis, also known as travel-related deep vein thrombosis (DVT), is an uncommon yet well-described condition. Similar to other topics I write about here, it can range from a minor inconvenience to (rarely) death, and is usually relatively easy to prevent.

In this article, I’ll walk you through what traveler’s thrombosis really is, why long-haul travel increases risk, who should be paying close attention, and, most importantly, how to prevent it using evidence-based strategies.

This is written from two perspectives: as a physician specializing in travel medicine and as someone who regularly flies long-haul.

If any of your flight tickets show travel time of 4 hours or longer, you should keep reading. If it shows 8 hours or more, you should DEFINITELY keep reading.

In This Article

What Is Traveler’s Thrombosis?

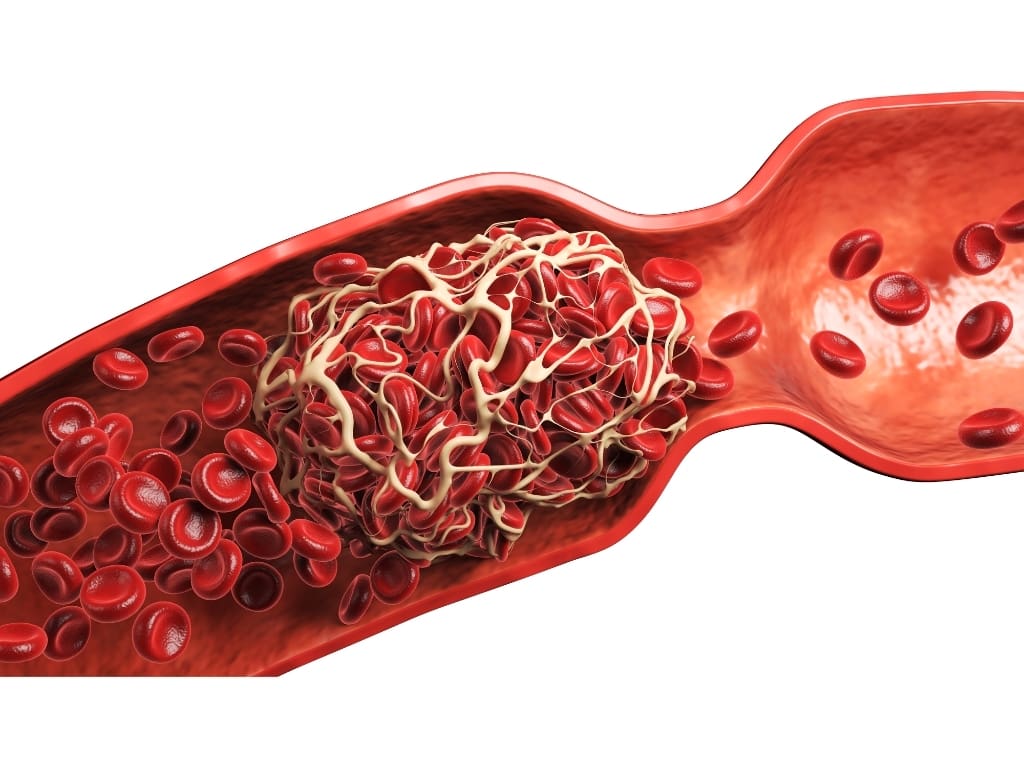

Traveler’s thrombosis refers to venous thromboembolism (VTE) – deep vein thrombosis with or without pulmonary embolism that occurs during or after prolonged travel, most commonly flights longer than four hours.

Despite the nickname “economy class syndrome,” this condition is not limited to airplanes or economy seats. The same risk exists with long car rides, buses, or trains. The unifying factor is prolonged immobility.

A clot typically forms in the deep veins of the calf or thigh. If part of that clot dislodges and travels to the lungs, it causes a pulmonary embolism (PE). Depending on the size of the clot and the area it ends its journey, it can cause no symptoms, shortness of breath, or even death.

The good news? The absolute risk is low.

The better news? With the proper knowledge, the risk becomes even lower.

Why Long-Haul Travel Increases DVT Risk

The pathophysiology of travel-related DVT is best explained by Virchow’s triad: venous stasis, hypercoagulability, and endothelial dysfunction. Long-haul travel hits at least one, and often two, of these mechanisms hard.

This model dates back to the 19th century, and although it is simplified and incomplete, it still explains the core mechanisms behind DVT.

First, venous stasis. Sitting for hours reduces calf muscle pump activity, slowing blood flow in the deep leg veins. Add seat-edge pressure behind the knees, limited legroom, and reluctance to get up, and stasis becomes significant.

Second, hypercoagulability. Many travelers already carry prothrombotic (favoring blood clot formation) risk factors: estrogen use, recent surgery, cancer, pregnancy. Travel doesn’t create risk out of thin air; it amplifies what’s already there.

Endothelial dysfunction means the inner lining of blood vessels stops functioning normally and instead favors clot formation. During long travel, conditions such as lower oxygen levels, low-grade inflammation, and sluggish blood flow can stress these vessel walls, making them less able to prevent clotting and more likely to contribute to its formation.

Lower cabin oxygen levels and dehydration have been studied, but immobility remains the dominant driver.

How Common Is Traveler’s Thrombosis?

Large epidemiological studies and WHO data show that long-distance travel roughly doubles to quadruples the relative risk of VTE. That sounds dramatic, until you look at absolute risk.

For healthy travelers, the risk is estimated at ~1 symptomatic VTE per 4,000–6,000 long-haul flights. Most events occur within the first 1–2 weeks after travel, with risk returning to baseline by 4–8 weeks.

Importantly, studies like the MEGA trial demonstrated that air travel is not uniquely dangerous. Long car, bus, or train journeys carry a similar risk. The main difference is that on other modes of transport, there’s usually more legroom and stops with the possibility of a short walk or a stretch. Meanwhile, airlines make their cabins increasingly crowded to offer cheaper tickets.

Symptoms You Should Never Ignore After Travel

Travel-related DVT often presents subtly. That’s part of the danger.

Common DVT symptoms include:

- Unilateral leg swelling

- Calf or thigh pain, tightness, or cramping

- Warmth or redness of the limb

Sometimes the first presentation is a pulmonary embolism.

PE symptoms include:

- Sudden shortness of breath

- Chest pain, especially with deep breaths

- Rapid heart rate

- Dizziness or loss of consciousness

Any of these symptoms within weeks of long travel should trigger urgent medical evaluation. Delay is what turns a treatable clot into a catastrophe.

Who Is Actually at Risk?

Most healthy travelers will never experience traveler’s thrombosis. The condition overwhelmingly affects people with pre-existing risk factors.

At the highest risk are those with:

- Prior DVT or pulmonary embolism

- Recent major surgery or trauma (6 weeks)

- Active cancer

Other high-risk groups include:

- Pregnancy or postpartum period

- Estrogen-containing contraception or HRT (40-fold increase*)

- Known thrombophilia or strong family history

- factor V Leiden (14-fold increase*)

- prothrombin (8-fold increase*)

- Obesity – BMI over 30 (3-fold increase*)

- Advanced age

- Severe mobility limitation

Risk is multiplicative, not additive.

A young woman on oral contraceptives might be at low risk. Add obesity, a window seat, and a 10-hour flight, and the equation changes.

* DVT and/or PE cases compared to a non-flying control without the specific risk factor. Data from the MEGA Study (Cannegieter et al., 2006)

Why Seat Choice, Height, and Clothing Matter

Small details matter more than people think.

Window seats are associated with a higher DVT risk (2-fold) than aisle seats because passengers move less. Obese travelers in window seats have shown a particularly elevated risk in studies.

Extremes of height also play a role. Very tall passengers (7-fold increase in passengers over 190 cm) often experience knee flexion and popliteal compression.

Shorter passengers (a 5-fold increase in those under 160 cm) may experience seat-edge pressure on the thighs. Both impair venous return.

Tight clothing, crossed legs, and under-seat luggage all restrict movement, further compounding the problem. These aren’t trivial lifestyle tips; they’re mechanical risk modifiers.

Prevention Starts With Movement (Non-Pharmacological Strategies)

For most travelers, movement is the single most effective prevention strategy.

Stand up and walk every 1–2 hours when possible. If you can’t, perform ankle pumps, heel raises, and calf contractions in your seat.

- Avoid sedatives that keep you immobile for the entire flight.

- Choose an aisle seat when possible.

- Wear loose, non-restrictive clothing.

Hydration is commonly recommended. While there’s some evidence that dehydration and alcohol didn’t raise the risk of blood clots, avoiding excessive alcohol and staying reasonably hydrated is sensible and low-risk.

These measures apply to everyone, regardless of risk profile.

Compression Stockings: When They Help and When They Don’t

Graduated compression stockings are one of the most evidence-supported preventive tools for travel-related DVT.

Randomized trials show they significantly reduce asymptomatic DVT during long-haul flights. The effect on symptomatic events is harder to prove because those events are rare, but the physiologic benefit is clear.

Who should use them?

- Travelers with moderate to high VTE risk

- Long flights (>6–8 hours) combined with risk factors

Who doesn’t need them?

- Low-risk travelers on short flights

Proper fit matters. True medical-grade knee-high stockings (15–30 mmHg of pressure at the ankle), measured to size, not generic “travel socks,” are what work.

Aspirin: Commonly Used, Poorly Understood

Many travelers reach for aspirin, thinking it prevents clots. This is understandable, and often misguided.

Aspirin is effective for arterial thrombosis but not for venous thrombosis. Its protective effect against DVT is limited, while bleeding risk remains real.

Major guidelines do not recommend aspirin for routine travel-related DVT prevention.

There is one narrow exception: in very high-risk individuals, when compression stockings or anticoagulation are not feasible, aspirin may be considered as a fallback.

Only the American Society of Hematology guidelines say this. Other American and British guidelines advise against the use of aspirin.

Anticoagulant Prophylaxis: Who Actually Needs It

Pharmacological prophylaxis is not for most travelers.

It is reserved for individuals at substantially increased risk, such as:

- Prior unprovoked or recurrent DVT

- Recent major surgery

- Active cancer

- Multiple strong risk factors combined

In these cases, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is the most evidence-supported option.

A typical regimen is a single subcutaneous injection of enoxaparin (e.g., 40 mg) on the day of travel, ideally a few hours (e.g., 4 hours) before the flight. This provides roughly 24 hours of anticoagulation and has been shown to virtually eliminate travel-related DVT in high-risk groups in studies.

Direct oral anticoagulants are sometimes discussed, but evidence for their use in travel remains limited.

Anyone considering anticoagulation for travel should consult a physician to weigh clot risk against bleeding risk.

Already on Blood Thinners? Here’s the Good News

If you are already taking anticoagulation for another reason (atrial fibrillation, prior DVT, mechanical heart valve), you are already protected.

No additional prophylaxis is usually required beyond standard movement measures.

Just ensure your dosing schedule aligns reasonably with travel timing.

Why Most People Worry Too Little, or Too Much

Traveler’s thrombosis sits in an uncomfortable middle ground.

Many people underestimate it entirely, dismissing leg swelling or breathlessness after travel. Others overestimate the risk, taking unnecessary medications or panicking over normal discomfort.

The truth is nuanced.

The risk is real, but predictable.

Low for most. High for some.

And prevention is remarkably effective when targeted correctly.

Summary: Key Takeaways

- Traveler’s thrombosis is rare but potentially serious

- Prolonged immobility is the main cause

- Risk depends heavily on individual factors

- Movement and compression stockings prevent most cases

- Medications are reserved for high-risk travelers

- Symptoms after travel should never be ignored

Traveler’s thrombosis is not about fear.

It’s about conscious movement, smart prevention, and knowing your personal risk.

As a physician and a frequent traveler, I don’t avoid long flights. I move, choose seats wisely, use compression socks when appropriate, and individualize prevention.

If this article changed how you think about travel health, explore my other blog posts on evidence-based travel medicine and preventive health strategies.

Share this with someone who often flies long-haul.

Use the advice before your next trip.

And travel smarter, so the only thing you bring home is memories.

Resources

Travel Medicine, 4th Edition – December 13, 2018, Authors: Jay S. Keystone, Phyllis E. Kozarsky, Bradley A. Connor, Hans D. Nothdurft, Marc Mendelson, Karin Leder, Language: English, Hardback ISBN: 9780323546966

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). CDC Yellow Book 2024: Health Information for International Travel. Oxford University Press.

Ahmedzai S, Balfour-Lynn IM, Bewick T, et al. British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee. Managing passengers with stable respiratory disease planning air travel: British Thoracic Society recommendations. Thorax 2011;66(1):S1–30.

Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis. 9th ed. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141(2):e195S– e226S.

Schünemann, H. J., Cushman, M., Burnett, A. E., Kahn, S. R., Beyer-Westendorf, J., Spencer, F. A., … & Wiercioch, W. (2018). American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood advances, 2(22), 3198-3225.

Clarke M, Broderick C, Hopewell S, et al. Compression stockings for preventing deep vein thrombosis in airline passengers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(9):CD004002.

Schreijer AJ, Cannegieter SC, Caramella M, et al. Fluid loss does not explain coagulation activation during air travel. Thromb Haemost 2008;99:1053–9.

Cannegieter SC, Doggen CJ, van Houwelingen HC, et al. Travel-related venous thrombosis: results from a large population-based case control study (MEGA Study). PLoS Med 2006;3:e307.

Kuipers S, Cannegieter SC, Middeldorp S, et al. The absolute risk of venous thrombosis after air travel: a cohort study of 8,755 employees of international organisations. PLoS Med 2007;4:e290.

Schreijer, Anja & Cannegieter, Suzanne & Doggen, Carine & Rosendaal, Frits. (2008). The effect of flight-related behaviour on the risk of venous thrombosis after air travel. British journal of haematology. 144. 425-9. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07489.x.

https://travelhealthpro.org.uk/factsheet/54/venous-thromboembolism

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this blog post is for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any health problem. The use or reliance on any information provided in this blog post is solely at your own risk.